In the newspaper business they have a saying that one picture is worth a thousand words. No matter how hard you try to describe a person or a scene, your portrayal can never come close to the accuracy of a camera. In the case of a musician, you could say that a minute of recorded sound is worth any number of words. How else can you convey a violinist's tone to someone who has never heard him? And if you have film of him, your task is made yet easier. Film cannot wholly replace the thrill of seiing and hearing a concert, but it can be a reasonable substitute. Strangely, film-makers were slow to appreciate the possibilities of capturing live music on celluloid. Many great musicians of the 1930s left us very little film of their playing or none at all, even though the means existed to make excellent documentary studies.

When, soon after the Second World War, Yehudi Menuhin was approached by the Hollywood producer Paul Gordon, the violinist immediately saw the potential of having some of his performances caught on film for posterity. He was so enthusiastic that it seems he worked for Gordon's Concert Film Corporation for very little money, banking on the movie making a profit and paying him royalties, such as he received for his sound recordings. His father, a much better businessman, was appalled, especially as he felt that Yehudi was dirtying his hands in having anything to do with Hollywood. The film, entitled Concert Magic, and featuring other artists besides Menuhin, was shot in the last months of 1947 at the studio formerly used by the comedian Charles Chaplin. Released about a year later, it was reasonably well received, but never caught on. Television was beginning to take over this sort of territory, and as a medium it was better able to present musical performances with immediacy and flair. Concert Magic has been virtually unseen for many years.

Yet Paul Gordon and his namesake Paul Ivano, the cameraman on the project, did an excellent job of presenting short pieces of music in a direct, unfussy manner. The film is very watchable, even though the other solo performers are not in Menuhin's class: the Polish pianist Jakob Gimpel, one of three brothers who at one time played as a trio, is some-what matter-of-fact in the way he delivers his solos; and the US contralto Eula Beal does not suggest that she is going to become a household word (nor did she). There is the usual quota of Hollywoodisms: the way the selections are introduced seems calculated to put a mass audience off, rather than convert it to classical music, and silly mistakes creep in. The pianist Adolph Baller – whose fingers were broken by the Nazis but who managed to recover well enough to be Menuhin's accompanist for a number of years – is said to be playing in the Bach prelude, which is for solo violin.

So the film is going to be watched for Menuhin's contributions, and they are excellent. An orchestra, presumably picked from the pool of West Coast musicians who worked in the film studios, is on hand to accompany some items, and the conductor is the Hungarian Antal Dorati, who frequently worked with Menuhin over the years. Bach's famous Air is performed in heartfelt fashion by the violinist, who also plays an obbligato for Eula Beal as she sings an aria from the St Matthew Passion in English. Menuhin and Baller begin suitably with the opening movement of Beethoven's First Violin Sonata. Then comes the famous prelude from Bach's Third Partita, followed by one of the violinist-composer Henryk Wienawski's most popular virtuoso pieces, the Scherzo-Tarantelle.

After the Bach aria we hear one of the most popular pieces by the great Italian violinist Paganini, his Moto perpetuo. Menuhin returns with Locatelli's Caprice No. 23, Il Labirinto Armonico, originally for solo violin but here with an accompaniment written by Mendelssohn's violinist colleague Ferdinand David. Then comes the Bach Air and then the Caprice No. 24 by Paganini, a solo violin piece which has inspired many other composers: it is heard in Fritz Kreisler's version with piano. Finally Menuhin plays Wilhelmj's arrangement for violin and piano of Schubert's song Ave Maria.

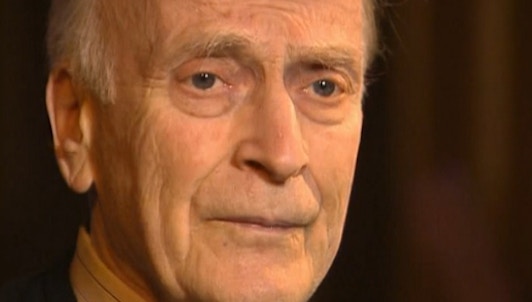

All the violin pieces will be familiar to those with a working knowledge of Menuhin's sound recordings, but it is invaluable to be able to see how he plays them. At the time the film was made, the violinist was at a crossroad in his life: his first marriage had broken up, he was embarking on a second marriage with the woman who would share the rest of his life, Diana Gould, and his carreer was finding its equilibrium again after the cataclysmic interruption caused by the war. During hostlities, Menuhin flew here, there and everywhere, usually in spartan military aircraft, giving concerts for the troops or simply cheering those on the home front with his music-making (his visits to Britain were eagerly anticipated). By the end of 1947 he was in his early 30s and approching his peak as a musician. In his prodigy days of the 1930s he had charmed people worldwide with his supremely natural playing, but had not gained enough experience of life to be able to plumb the depths of interpretation. Now, with his handsome profile, deeply serious commitment and warmth of tone, he was ready to win over a new generation with his musicianship. It is fascinating to encounter him on film at this juncture, even if the music consists only of short pieces. Menuhin never played dross and he enhanced even the popular pieces in his repertoire with his power of illumination.