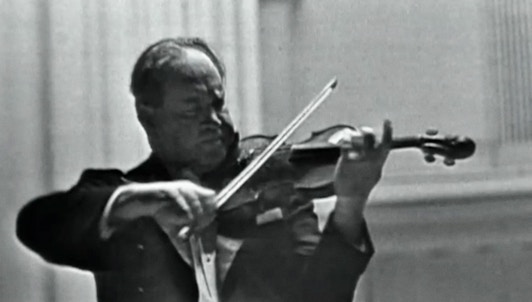

David Oistrakh, the violin legend, under Stalinist terror.

"How ever hard I try, I can't recall ever having been without a violin during my childhood. I was three and a half when my father brought home a toy violin for me. As I played it I imagined I was a street violinist, a poor man's occupation that was widespread in Odessa at the time. But I could not imagine any greater happiness." The little prince, adored by his mother ("Do you know why he is so intelligent? Because, as a child, he bathed in my milk!") became for all of his fellow musicians "King David," a title he came to merit.

Bruno Monsaingeon tells the violinist's from his birth in Odessa in 1908 until his death from a heart attack, in Amsterdam in 1974. But it is a story marked by tragedy, because it mostly takes place under Stalin: "I remain loyal to Russia, to the country, irrespective of who is in power." This choice, which his friend Shostakovich also made, had terrible consequences which combined fear and compromise. "The regime forced people to have two faces, to think in one way and to appear in another," said Rostropovich. Oistrakh, who lived in dread of being arrested, became, in spite of himself, a propagandist for the regime. Until Stalin's death in 1953, he wasn't allowed to play on the other side of the Iron Curtain. But according to Rostropovich, who experienced this dark period: "For us music was the only window onto the sun, oxygen and life."

Menuhin, Rostropovich and Rozhdestvensky, who knew him well and played with him, talk of his "delightful" nature and of his incomparable talent which we are able to appreciate thanks to prodigious sound archives. The testimony of his son Igor, also a violinist and a great teacher, is just as precious because of what it reveals about the man behind the art.

And there is a miraculous find: the telephone conversation recorded between Oïstrakh and Shostakovich after the violinist had premiered—that very evening—the Violin Concerto No. 2, written for him by the composer. From his hospital bed Shostakovich had heard the concert on the radio. "Your interpretation is fantastic," he said to him. "I'm going to make you a foolish compliment: It's as if I had played it myself." Oistrakh: the music man.

Enhanced with exclusive, never-before-seen commentary by the director.