In his career, Cecil Taylor went from being a classically-trained piano prodigy to the father of free jazz. The intervening period, where he cut his teeth as a concert performer and jammer, took place in the 1950s. He saw the tail end of bebop and the dawnings of post-bop and yet, even on those early recordings, contemporary critics sensed a different sense of freedom emerging from his playing style.

Fast-forward into the early 60s and Taylor was, to all intents and purposes, out on an artistic limb, creating music that was increasingly more complex and untethered. He wasn't toeing the line, he was weaving his own as he went, inspired by the spirit of Charlie Parker, combining a blues sensibility with avant-garde music that just about fit the blurry outline of the jazz tradition.

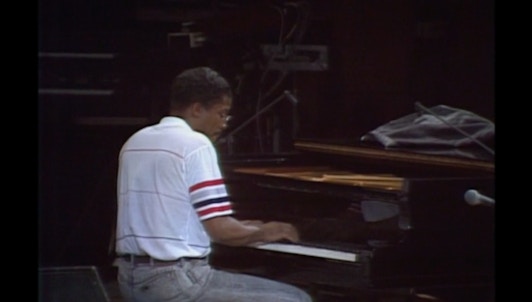

By the time of this 1984 performance, Taylor's contributions to music had been recognised and he was seen as a forebearer, as one of the artists who had reclaimed the fiery, elusive and essential elements of jazz and related music from the clasps of the mainstream. That evening, the Munich audience got to see Taylor in full flow, demonstrating how, to him, "the piano in itself is an orchestra."