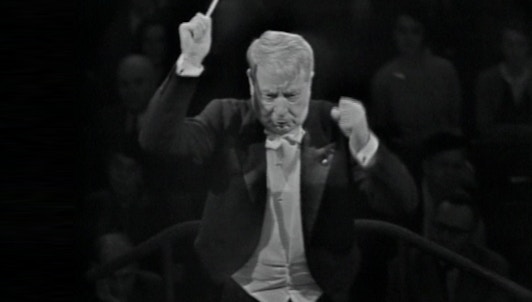

Leinsdorf, conducting from memory and without baton, secures a performance that is brisk, but not headlong in the Munch manner. It is clear that he has paid attention in rehearsal – and continues to pay attention in performance – to details of articulation, the clear definition of rhythms, and matters of balance, but he does not stand in the way of the expressivity of his principal players – in this piece, oboist Ralph Gomberg in particular.

In one of his books, Leinsdorf draws a distinction between conductors who merely handle traffic and conductors who make music. His traffic-handling is meticulous, and he controls every transition between tempos expertly. He is not fun to watch in the way that many post-Bernstein conductors are; his attention is directed to the orchestra and the music. (Leinsdorf commented pertinently on the baleful influence of television on conducting. In his view, conductors have begun to play to the camera as well as to the orchestra and the audience.) On the other hand, it is extremely interesting to watch a clear, virtuoso technique in action; everything Leinsdorf does with his hands conveys information to the players. His face, on the other hand, is often expressionless, and even in the most impassioned moments communicates only a modified rapture; he does permit himself a hint of a smile at the successful close of the second movement. Schumann's Fourth Symphony was a particular favourite of Leinsdorf's, which he recorded with the BSO for RCA despite the company's objections that it wouldn't sell. For his performances of the Schumann Symphonies, Leinsdorf preferred to use the emendations Mahler made to clarify the composer's somtimes murky orchestration, though he refused to accept Mahler's occasional recompositions.

His performance is slower and less driven than some, but no less intense; his face does glower in this sometimes rather stern symphony. There are some amusing moments in the finale, when Leinsdorf's hands seem to be listening and responding to each other, although what they are doing in fact is laying out the conversation within the orchestra. The new concertmaster, Joseph Silverstein, spins out his solo in the Romance beguilingly.

In 1963-1964, the BSO telecasts moved to Symphony Hall, where it was possible to arrange better lighting and more sophisticated camerawork. Parsifal is an opera Leinsdorf conducted nineteen times at the Met between 1938 and 1960; he also led it at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires. Excerpts from Parsifal, and sometimes an extended orchestral work he assembled from several parts of the opera, were a part of Leinsdorf's standard repertory for his guest-conducting engagements, and at the end of his life, he recorded his Symphonic Excerptsfrom Parsifal with the South-west German Radio Orchestera. (Curiously, Roger Norrington has also recorded Leinsdorf's collage).

On this occasion, in Symphony Hall, Leinsdorf led only the Good Friday Music from Act Three in Wagner's own orchestral version. This performance dispels the myth that Leinsdorf was merely an expert mechanic. The Warmth of sound and flexibility of phrase are a compelling illustration of how completely attuned he was to everything in Wagner's vision that is spiritual, miraculous and numinous.

Source: Richard Dyer/ICA